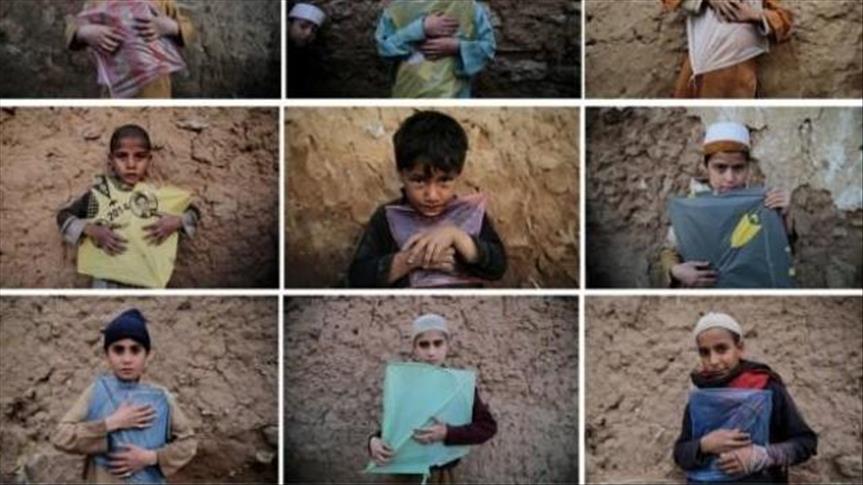

Karachi, Pakistan, 3 Jumadil Akhir 1437/12 March 2016 (MINA) – In the narrow dust-choked streets of Pakistan’s textile hub Faisalabad, police chase children as they run after kites cut down in battle.

From the rooftops, revelers watch the kite fights, the centerpiece of the spring-welcoming festival known as Basant.

The image of the kite fight was popularized by the best-selling novel The Kite Runner, set in neighboring Afghanistan. It was a Taliban ban that pushed author Khaled Hosseini to write the novel, published in 2003, Anadolu Agency quoted by Mi’raj Islamic News Agency (MINA) as reporting.

In recent years, the game has been suffering from bans in Pakistan, where the government has deemed it dangerous.

Also Read: Pakistan Declares State of War After Car Bomb Incident

In the last 10 years, the deaths of hundreds of people – mostly children – has forced authorities to ban the centuries-long tradition meant to welcome the spring.

The deaths coincided with a period when the festival had become increasingly popular in Pakistan, spreading from its historical home in Lahore to the rest of the country.

But the sharp, often metal, strings used to detach kites during competitive kite fights have killed several children by cutting their throats, sparking country-wide anger that has forced the government to ban the festival from taking place in major cities.

The more kites one picks, the more praise he concedes from his colleagues. And more significantly, the “looted” kites are bought by the village elders and revelers at a good price.

Also Read: Jakarta Hosts Gala Dinner for World Peace Forum Delegates

The dual temptation for money and praise propels more children and young boys to run for the kites, which sometimes turns out to be a bloody affair.

Apart from fatal road accidents and stampedes during the run, there have been bloody clashes between the boys claiming their respective rights on landing kites.

“According to the rules, the one who touches or catches the string of the landing kite wins. But sometimes two or three runners touch the string at the same time, which often turns into a clash”, Zulfikar Hussein, a Faisalabad-based kite maker, told the Anadolu Agency.

For many, especially in northeastern Punjab, the country’s largest and richest province, kite flying runs in their blood as is seen during the months of February and March where the skies are decorated with kites.

Also Read: Indonesian Minister Urges Synergy Between Wasathiyah Islam and Chinese Wisdom

But for many, the ban does not quench the passion for the controversial sport.

Skies are filled with kites in several cities of Punjab despite a major police crackdown in which over 200 revelers were arrested in recent days.

“No one is against healthy sport. But kite-flying is a death sport,” Rishad Hussein, a resident of Lahore, told the Anadolu Agency, referring to hundreds of deaths in throat-slitting incidents due to the sharp metal strings.

Last month, Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif suspended a city police chief after a girl was badly injured by a sharp string in Gujranwala district.

Also Read: New Delhi Covered in Toxic Smog: Residents Say ‘We Can Hardly Breathe’

Several others have been injured in different parts of the province despite a ban on the sport.

Basant was taken to its zenith by the country’s former military ruler General Pervez Musharraf, who made it an international event between 2004 to 2008.

The occasion promoted Lahore as the country’s cultural hub and prompted citizens to rent out the roofs of their homes for use in kite-flying events throughout the month.

Some events, this year, have been organized on Lahore’s outskirts, but enthusiasm for this limited form of the traditional festival is muted.

Also Read: Boat Carrying 100 Rohingya Migrants Capsizes in Malaysian Waters

“I will be the last person to support the lifting of the ban on this blood-sport after seeing the slit throats of children,” an emotional Hussein said.

Supporters of the sport, however, argue that the Basant festival not only generates economic activity, but also portrays a soft image of the country worldwide.

“Kite-flying has never been a dangerous sport till people started using metal and other banned strings. It is a minority group of people that were involved in the violation,” Ghulam Mustafa, a kite-seller, told Anadolu Agency. “Banning such a healthy and traditional activity just because of the violation of a small group is unjust and unfair.” (T/P010/R07)

Mi’raj Islamic News Agency (MINA)

Also Read: Dozens Killed in RSF Drone Strike on Sudanese Village During Funeral

Mina Indonesia

Mina Indonesia Mina Arabic

Mina Arabic